In May, 2010, I was a resident artist and performer for artist Theaster Gates’ piece, Cosmology of Yard, at the Whitney Biennial. I and two other artists, Torkwase Dyson and Dara Epison, were given the freedom to reinvent Gates’ wood-clad Cosmos in the Whitney Sculpture Court. Over the course of three separate ten-day residencies we were given the challenge to reinterpret, expand, and respond to Gates’ installation. The Monastic Residencies in conjunction with Gates’ Cosmology of Yard were formed collaboratively out of a common interest in transforming space, bridging understanding, and challenging ideas of collaboration and creative ownership. The Monastic Residency, Counting Time, included a durational performance, works on paper, ink drawings, and temporary interventions to the space. Interventions were made to encourage audience participation and activate underused areas of the courtyard. The modular wooden boards were painted on and used as props for drawings and installations. They were also rearranged daily to change the flow of foot traffic and sight lines of visibility in the courtyard space.

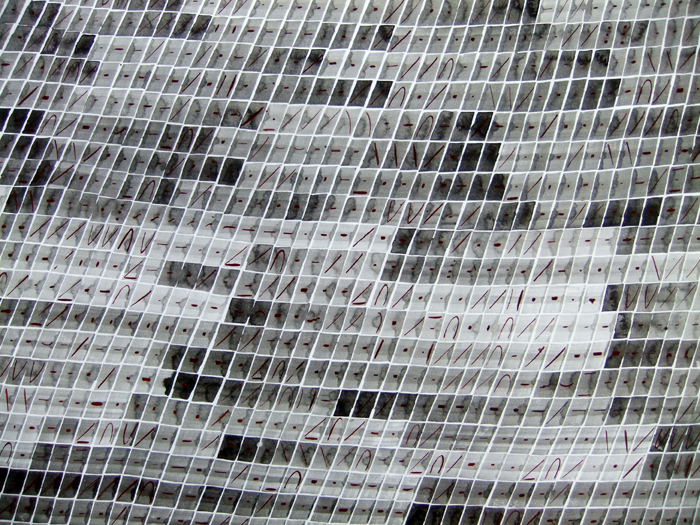

Being/Becoming took place continually from the museum hours of twelve to six (pm) for ten days. Performance times ranged from a few minutes to as long as two hours. The residency acted simultaneously as a time for production and a site for performance. Within a 110 x 110 piece of paper the monk would each day perform the act of painting. The monk would paint according to two methods of operation. The first method was implemented when the monk was alone in private practice. The method involved painting an abstract composition into each individual grid. The monk would repeat and vary these compositions to form a script. The monk pulled freely from a mental catalog of universal abstract shapes and symbols. Overtime the random script would become a meaningless code about nothingness. This method was open to the wandering mind and subjectivity of the performer. This aspect of the performance was an attempt to come to a new awareness and understanding achieved through meditative focus, repetition, and the act of painting. The marking of the grids also became a record of the monk’s time in residence.

Audiences were invited to interrupt the monk in progress. The monk would break the random writing of code when this interruption happened. He would then implement the second method of operation. A predetermined mark was then made to record the monk’s movement from the private into the social. This same mark was inserted into the code each successive social interaction. Relying on chance this method utilized the randomness of the courtyard rather than the performers subjectivity. It became a visual map of each time the monk engaged with the public over the ten-days.

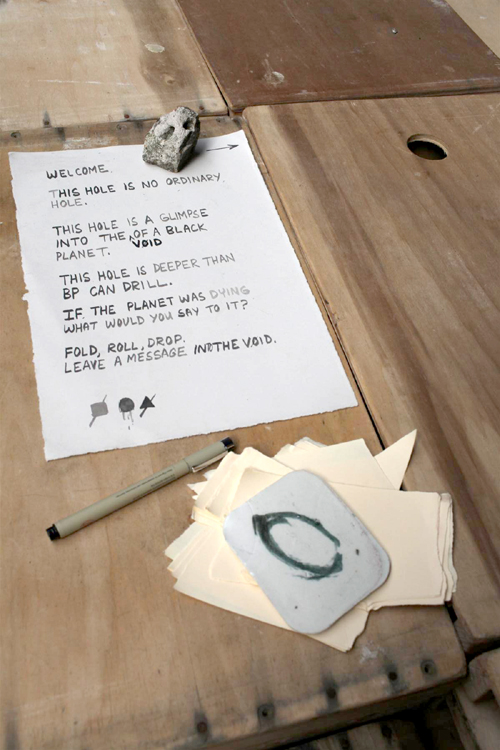

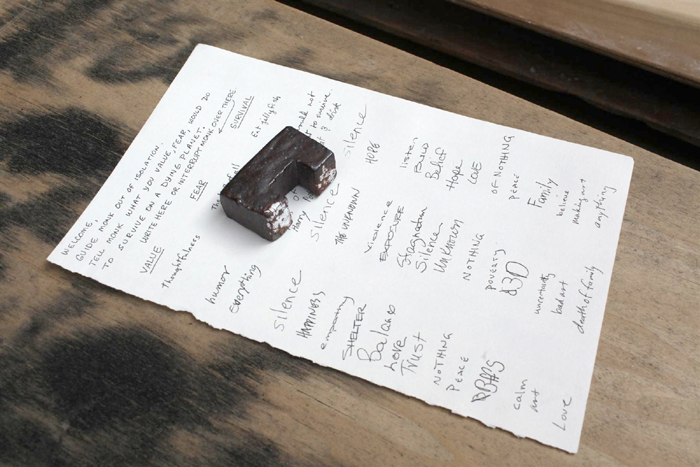

The participation of the audience became an integral part of the monk’s process. The audience acted as a guide to bring the monk out of isolation. A discrete text piece prompted the audience to share with the monk, “What would you value, fear and do to survive on a dying planet?” The monk’s willingness to step out of painting space came unexpected to some visitors. The performer would often explain, that ultimately, the painting was a tool to encourage engagement with the public.

Wearing a silver robe, the monk could be seen painting on his knees from the street above. Looking into the courtyard, loud droning chants could be heard from Gates’ video installation. Immersed in the black gradation of the painting surface, the monk might appear dislocated from specific time and place. The monk was seemingly familiar but also foreign. The monk acted out painting rituals influenced by ancient Tibet practices while wearing a robe influenced by the afro-futuristic clothing of Sun-Ra. Interested in ideas regarding authenticity, the performer played with contradictions of the past, present, and future. Some of the more humorous and interesting interactions occurred when visitors believed the artist to be an actual monk. Carrying certain expectations some viewers were confused or disappointed when realizing this was not the case. For others, this opened up a space for dialogue. It was during these interactions some of the most enlightening and rewarding moments occurred.

Conversations ranged from answering questions about the artwork to the more personal. Some openly expressed their like, or dislike, for the work. Some visitors offered their thoughts about New York and the New York art world. Most were simply curious about what the performer was doing and why. Many generously responded to the text prompts by sharing their thoughts on fear, value, survival, and their concerns about the current British Petroleum oil spill. Some visitors discussed their own spiritual practices and the role it played for them in face of uncertain and misguided times. Others were more responsive to the lists and left behind hand written messages. Sometimes people simply gave a look of acknowledgment or a smile. For the performer, the experience was a challenge in humility, consistency, and extroversion. It was also a lesson in trust and openness to the audience. At the close of the ten days the monk rolled up the scrolls and uninstalled the space. The painted “Welcome” boards were left behind as the only remnants of the monk’s time in residence.